Agnapostate

Well-Known Member

If possible, I'd like commentary on the nature of an ideology that advocates civil rights and liberties for youth that are capable of handling them, and effectively promotes replacing age restrictions with some other standard of competence measurement. The nature of these "youth rights," which are a component of a broader platform of youth liberation, can be effectively summarized in the educator John Holt's (Escape From Childhood, New York: E. P. Dutton, 1974) proposal, in which he declared:

Now, the most obvious and ever present objection would be the incompetence and immaturity of adolescents and their inability to exercise such rights and responsibilities, let along younger children. But to put this in perspective, I typically quote Joshua Meyrowitz (The Adultlike Child and the Childlike Adult: Socialization in an Electronic Age, Daedalus, Vol. 113, No. 3, Anticipations (Summer, 1984), pp. 19-48) in an attempt to illustrate the nature of "childhood" as having somewhat fluid boundaries that are widely varying among time and place in both chronological terms (set age restrictions), and the precise nature of limited rights granted to those considered "children."

It's the modern conception of childhood itself that forms the basis behind the popular perception that children and adolescents are incapable of competently exercising the rights and responsibilities that adults currently possess, by creating a popular negative image of them based on several misconceptions. As the psychologist Richard Farson (Birthrights, New York: Macmillan, 1974) notes:

However, we know for a fact that the concept of childhood has undergone dramatic structuring and restructuring over the past few centuries, with many of our current stereotypes about modern youth being based on the consequences of previous infantilization of them. For example, the modern Western institution of adolescence is an example of an artificial extension of childhood that has only existed since the period of the Industrial Revolution or so. The point is driven home by Frank Fussell and Elizabeth Furstenberg in The Transition to Adulthood During the Twentieth Century: Race, Nativity, and Gender.

Moreover, the education author (and former New York City Teacher of the Year) John Taylor Gatto (The Underground History of American Education, New York: Odysseus Group, 2001) elaborates on this matter, writing the following:

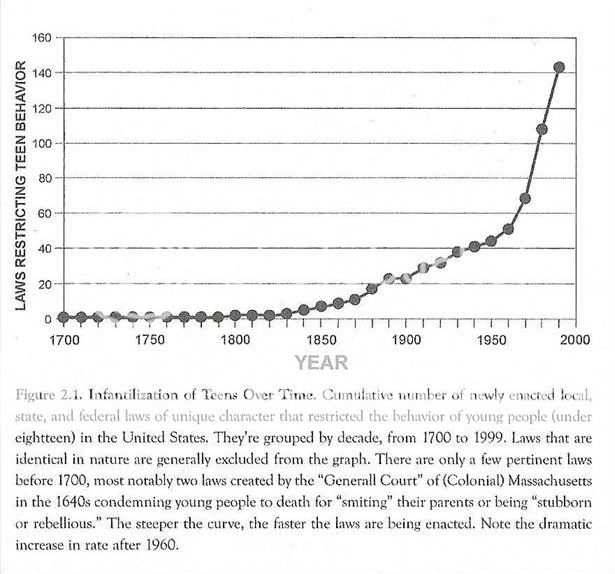

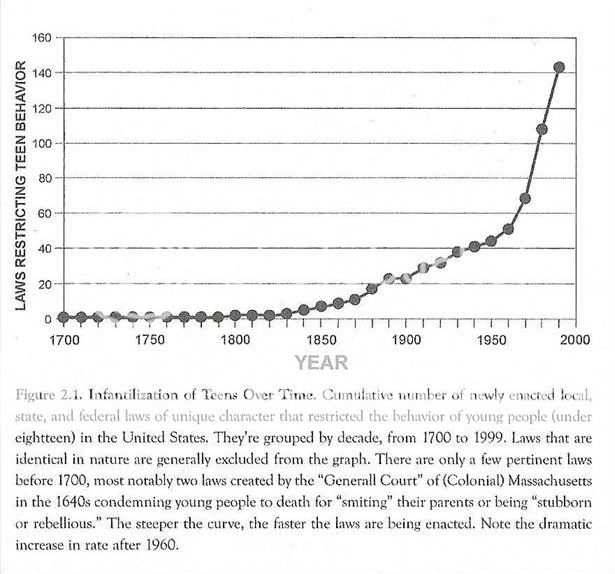

Gatto's statement notably incorporates acknowledgment of the reality that the establishment of adolescence wasn't necessarily based on the purest motives, and some had an interest in gaining from the infantilization of youth, most obviously those who gained from the elimination of able-bodied youth from the workforce and effective imprisonment in school elaborated on by Fussell and Furstenberg (sorry about the crooked graph.)

The most recent major elaboration on this effective infantilization of youth that has occurred has come from the American psychologist Robert Epstein (The Case Against Adolescence: Rediscovering the Adult in Every Teen, New York: Quill Driver Books, 2007). As he writes:

He includes this accompanying image to further illustrate the reality that the establishment of adolescence over the past century and a half involved the establishment of new age restrictions on adolescents that had not previously existed in American society:

Now, this alone obviously can't justify the elimination of adolescence or any other component of modern childhood as a phase of the life cycle, especially in light of claims that age restrictions served as protections for youth in a turbulent world that they lacked sufficient competence to deal with. These summaries offered thus far are intended to serve as explanations rather than justifications, and intended to offer a descriptive observation rather than a prescriptive recommendation. It's thus necessary to highlight a crucial difference between *is* and *ought*. And some authors (notably Neil Postman) who concede that childhood and adolescence are effectively inventions (to some extent) of the past few centuries note this not to claim that they necessitate abolition or elimination, but to claim that they're beneficial establishments of life phases that properly train and condition youth for adult life.

However, recent authors have disputed this, and have focused on some of the same dramatic restructuring of childhood that Holt proposed, this time with a specific focus on adolescence. As Epstein puts it:

I propose...that the rights, privileges, duties, responsiblities of adult citizens be made available to any young person, of whatever age, who wants to make use of them. These would include, among others:

1. The right to equal treatment at the hands of the law-i.e., the right, in any situation, to be treated no worse than an adult would be.

2. The right to vote, and take full part in political affairs.

3. The right to be legally responsible for one's life and acts.

4. The right to work, for money.

5. The right to privacy.

6. The right to financial independence and responsibility-i.e., the right to own, buy, and sell property, to borrow money, establish credit, sign contracts, etc.

7. The right to direct and manage one's own education.

8. The right to travel, to live away from home, to choose or make one's own home.

9. The right to receive from the state whatever minimum income it may guarantee to adult citizens.

10. The right to make and enter into, on a basis of mutual consent, quasi-familial relationships outside one's immediate family-i.e., the right to seek and choose guardians other than one's own parents and to be legally dependent on them.

11. The right to do, in general, what any adult may legally do.

Now, the most obvious and ever present objection would be the incompetence and immaturity of adolescents and their inability to exercise such rights and responsibilities, let along younger children. But to put this in perspective, I typically quote Joshua Meyrowitz (The Adultlike Child and the Childlike Adult: Socialization in an Electronic Age, Daedalus, Vol. 113, No. 3, Anticipations (Summer, 1984), pp. 19-48) in an attempt to illustrate the nature of "childhood" as having somewhat fluid boundaries that are widely varying among time and place in both chronological terms (set age restrictions), and the precise nature of limited rights granted to those considered "children."

[T]hose who insist upon the "naturalness" of our traditional conceptions of childhood are basing their belief on a very narrow cultural and historical perspective. Childhood and adulthood have been conceived of differently in different cultures, and child and adult roles have varied even within the same culture from one historical period to another.

It's the modern conception of childhood itself that forms the basis behind the popular perception that children and adolescents are incapable of competently exercising the rights and responsibilities that adults currently possess, by creating a popular negative image of them based on several misconceptions. As the psychologist Richard Farson (Birthrights, New York: Macmillan, 1974) notes:

As childhood became more important, society for the first time began associating it with all sorts of negative qualities: irrationality, imbecility, weakness, prelogicism, and primitivism. It is difficult for our present culture to appreciate that these demeaning views of children are a recent development, appearing only after childhood acquired increased significance. And with this new importance, came, for the first time, antipathy toward the child, the beginnings of our present resentment.

However, we know for a fact that the concept of childhood has undergone dramatic structuring and restructuring over the past few centuries, with many of our current stereotypes about modern youth being based on the consequences of previous infantilization of them. For example, the modern Western institution of adolescence is an example of an artificial extension of childhood that has only existed since the period of the Industrial Revolution or so. The point is driven home by Frank Fussell and Elizabeth Furstenberg in The Transition to Adulthood During the Twentieth Century: Race, Nativity, and Gender.

The lives of 16-year olds in 1900 and 2000 could hardly be more different. In 1900 the term "adolescent" had barely been coined, much less popularized (Chudacoff 1989)...The status combination of attending school, living in the parental home, and remaining single and childless characterized only 40% of white 16-year olds in 1900 but grew to over 70% of this group by 1940, finally reaching about 90% by 2000.

Moreover, the education author (and former New York City Teacher of the Year) John Taylor Gatto (The Underground History of American Education, New York: Odysseus Group, 2001) elaborates on this matter, writing the following:

During the post-Civil War period, childhood was extended about four years. Later, a special label was created to describe very old children. It was...adolescence, a phenomenon hitherto unknown to the human race. The infantilization of young people didn't stop at the beginning of the twentieth century; child labor laws were extended to cover more and more kinds of work, the age of school leaving set higher and higher. The greatest victory for this utopian project was making school the only avenue to certain occupations. The intention was ultimately to draw all work into the school net. By the 1950s it wasn't unusual to find graduate students well into their thirties, running errands, waiting to start their lives.

Gatto's statement notably incorporates acknowledgment of the reality that the establishment of adolescence wasn't necessarily based on the purest motives, and some had an interest in gaining from the infantilization of youth, most obviously those who gained from the elimination of able-bodied youth from the workforce and effective imprisonment in school elaborated on by Fussell and Furstenberg (sorry about the crooked graph.)

The most recent major elaboration on this effective infantilization of youth that has occurred has come from the American psychologist Robert Epstein (The Case Against Adolescence: Rediscovering the Adult in Every Teen, New York: Quill Driver Books, 2007). As he writes:

Adolescence is the creation of modern industrialization, which got into high gear in the United States between 1880 and 1920. For most of human history before the Industrial Era, young people worked side by side with adults as soon as they were able, and it was not uncommon for young people, and especially young females, to marry and establish independent households soon after puberty. It wasn't until the turn of the twentieth century that adolescence was identified as a separate stage of life characterized by "storm and stress." In what appears to be a vicious cycle of cause and effect, teen turmoil since the late 1800s has generated a large number of unique laws that restrict teen behavior in ways that adult behavior has never been restricted, and these laws in turn appear to have stimulated more extreme forms of "misbehavior" in teens. The rate at which such laws have been passed has increased substantially since the 1960s, with an increasingly wide range of new crimes being invented just for young people. The social reforms that created such laws were set in motion by some formidable individuals, not all of whom had benevolent motives. The extension of childhood past puberty has benefited a large number of new businesses and industries offering a wide range of products and services to the growing teen markets.

He includes this accompanying image to further illustrate the reality that the establishment of adolescence over the past century and a half involved the establishment of new age restrictions on adolescents that had not previously existed in American society:

Now, this alone obviously can't justify the elimination of adolescence or any other component of modern childhood as a phase of the life cycle, especially in light of claims that age restrictions served as protections for youth in a turbulent world that they lacked sufficient competence to deal with. These summaries offered thus far are intended to serve as explanations rather than justifications, and intended to offer a descriptive observation rather than a prescriptive recommendation. It's thus necessary to highlight a crucial difference between *is* and *ought*. And some authors (notably Neil Postman) who concede that childhood and adolescence are effectively inventions (to some extent) of the past few centuries note this not to claim that they necessitate abolition or elimination, but to claim that they're beneficial establishments of life phases that properly train and condition youth for adult life.

However, recent authors have disputed this, and have focused on some of the same dramatic restructuring of childhood that Holt proposed, this time with a specific focus on adolescence. As Epstein puts it:

Young people should be extended full adult rights and responsibilities in each of a number of different areas as soon as they can demonstrate appropriate competence in each area. Passing appropriate tests will allow competent young people to become emancipated, start businesses, work, marry, and so on, but I am not suggesting that young people be given more "freedom."